Singapore, a bustling city in Asia, is well-known for its ideal living conditions despite having a high population density. Residents here have benefited from reasonable urban planning, which has allowed them to enjoy tangible outcomes such as a prosperous economy, splendid liveability, efficient transportation system, and a sustainable ecological environment.

Beyond these benefits, planning also acts as an invisible hand, silently shaping the distinctive lifestyle and unique qualities of the city’s residents. This impact is especially felt by generations that have grown up in an urban setting. They are different from the older generations before them who have witnessed the country progress from a third world to first world nation, and are unlike foreign talents who have already become accustomed to a certain lifestyle before relocating to Singapore.

The generations that have grown up in the city are adapted to living in an orderly manner — a lifestyle yielded by good and reasonable planning. As a result, these generations amassed some unique traits that became the forces behind a virtuous circle driving the continuous development of Singapore.

1. The orderly lifestyle

Singapore’s urban planning is highly systematic and hierarchical. This is consistent across road systems, commercial buildings, as well as residential estates and supplementary facilities. Take commercial entities for example, the facilities are clearly an ordered approach.

Basic, common premises that are patronised daily such as food courts, supermarkets, and provision shops are located nearest to the residential areas. Slightly higher-tiered facilities that receive weekly patronage such as wet markets, pharmacies, hair salons, optical shops, and small eateries are located in the heart of each precinct, and within walking distance from home. Facilities of the next tier that do not require much frequenting, such as banks, book shops, posh restaurants, and office premises are located at the centre of each new town. Residents from the new towns can choose to walk or take a bus, which brings them to these facilities within 20 minutes.

At the same time, these new towns are equipped with supporting facilities ranging from libraries and clinics, to elderly homes. Facilities of the highest tier will be located near the city centre, where people who visit them only occasionally would not find the distance too great.

Such planning has shaped the lifestyles of many families unknowingly. People drop by supermarkets or food courts to grab their meals before returning home after school or work; children visit the playground after school; families visit the neighbourhood park or shop around the malls in the new towns over the weekends, and head to the city centre to dine, socialise, or even visit attractions once or twice a month.

This organised rhythm in life and convenience is crucial for the youngsters. Without a sudden traffic congestion or the need for a long commute to access facilities, there will be minimal disruptions to their schedules. Furthermore, they will be extremely familiar with their precinct, meaning the world outside their homes is not one that is too foreign or intimidating.

A majority of the local residents have gotten too comfortable with the aforementioned scenarios; however, and can only begin understanding and appreciating their organised lifestyles after experiencing the chaos in other cities.

With working from home becoming a new integral part of everyday life in this pandemic, the convenience of an ideal community setting is further accentuated. Besides, restrictions on time spent outdoors mean greeting fellow residents might be one’s only chance to socialise for the entire day. Meanwhile, food courts, parks, and playgrounds grant a respite to those who have dutifully stayed home. For the younger generations, this pandemic may have robbed them of travel opportunities, but Singapore’s well-organised communal living has instead offered them the opportunities to appreciate and interact with nature.

2. Love and embrace nature

Asia is the most densely populated continent in the world. Developments in areas of high densities have caused younger generations to grow up in concrete jungles, with minimal knowledge about a natural environment. Fortunately, the younger generations in Singapore do not lack the opportunities to connect with nature despite having grown up in a densely populated city.

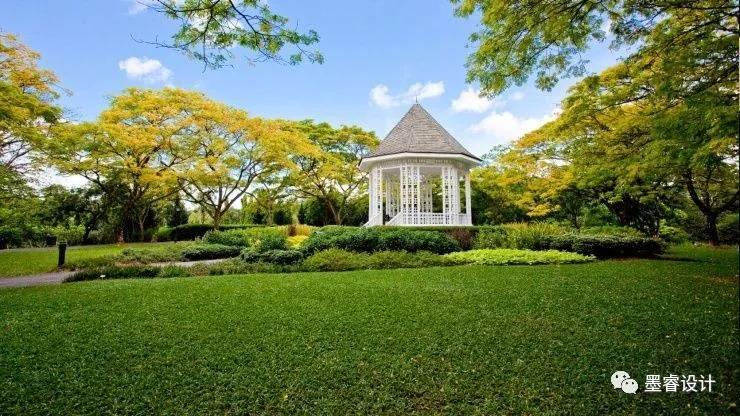

Singapore still preserves large amounts of ecological spaces, albeit severely land constrained. These ecological spaces do not simply serve as artificial parks in the city but more importantly, they preserve the nature reserves and parks in their original ecological states to support biodiversity and preserve a portion of unmodified nature. At the same time, more than 300 kilometres of greenway connects nature with residential areas. The elements of this tropical environment, such as the reservoirs, jungles, hills, and beaches, cultivate the affection and respect for nature while the children are having fun.

It is worth noting that Singapore’s planning does not halt here. In the city’s blueprints for its future, parks will be within a walking distance of 400 metres for 80% of families — a feat feasible only through reasonable planning. Concurrently, the government has decided to integrate carbon-neutral architecture in schools, to achieve the goal of having one-fifth of campuses being carbon neutral by 2030. This translates into a fifth of its student population having the opportunity to experience first hand how to reduce carbon footprints. The mindset of energy conservation will then start to cultivate amongst the younger generations.

3. Emphasis on preserving history and culture

Dr. Liu Thai Ker, MORROW’s founding director and my teacher in urban planning, once mentioned that he does have some regrets despite being proud of his planning contributions to Singapore. He cited one of them as not being able to preserve some of Singapore’s earlier towns for the lower income group.

When Singapore first gained independence in 1965, shanty towns were a common sight with approximately 250,000 people living in them, and at least 11 families squeezed into a single shop house. Such living conditions will certainly be unimaginable to the younger generations who have grown up living in comfortable HDB flats (Singapore’s public housing) or even private condominiums. Sadly, these slices of Singapore’s history have since been slowly forgotten by the people.

Urban planning and construction often bring about changes to a city. Pieces of the memories of the past gradually fade out from the lives of people as the city develops, leaving future generations with a low likelihood of experiencing these histories and cultures. The big question is, how can they spot traces of a city’s past when they live in such a highly-modernised city? This is when inclusive urban planning and preservation of history are of utmost importance.

With conservation measures and principles detailed in the early stages of planning, it ensures the preservation of architectures and streets that have historical and cultural significance, as well as natural environments. All this, while driving efficient modernisation.

Many Chinese cities have histories dating back at least a century, with some even exceeding a thousand years. In spite of the duration, countless ancient architectures were carefully preserved. In contrast, Singapore, a tiny red dot on the world map, only has around 50 years of history in urban planning and construction, and certainly does not have any century-old architecture. However, planners from the earlier days of Singapore have still managed to preserve many precious memories throughout this short but well-paced development.

Before deciding whether the architecture-of-interest should be preserved or torn down, a comprehensive analysis is first conducted to assess its contribution to the social, economical, and cultural development, regardless of the architecture type — historical buildings, old streets, or contemporary architecture districts. In other words, the quality of the architecture and age of the building are not the only measurements to determine if the architecture-of-interest should be retained or scrapped.

In recent years, decisions to tear down modern symbolic architectures, such as the Pearl Bank Apartment and the Shaw House for redevelopment have stirred up huge debates. This shows the amount of emphasis that Singaporeans place on preserving such architectures, pushing the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) to consider how to inject new life into these modern architectures built in the early days of Singapore’s development. Thankfully, one such building — the Golden Mile Complex — was successfully preserved, which was heartwarming news indeed.

This series of measures allow the younger generations to understand the efforts their ancestors have put into city building, and provide them the opportunity to learn about the urban development process. It is heartening to see historical districts such as Telok Ayer Street and Kampong Glam emerging as trendy and heritage-rich central districts that appeal to the younger patrons. Through engaging in appropriate preservation and injecting new values and functions into these places, it also silently cultivates a sense of resonance with the histories of ethnic cultures and ancient buildings among the younger generations.

4. A strong sense of national identity

Singapore’s planning is a perfect example of the fusion of various ethnic cultures. While Singapore has managed to avoid racial conflicts with proper planning and policy implementations, many developed countries continue to suffer from these conflicts resulting from the formation of ethnic enclaves in the cities.

When formulating policies, authorities should look beyond the ethnic characteristics of historical districts and be mindful of the end goal — to achieve ethnic integration in all parts of a city. This is especially so for HDB residential areas. By encouraging different ethnic groups to live within the same neighbourhood, the younger generations will be familiar with interactions between people of different ethnicities while growing up. For this reason, they should then better embrace people of different racial backgrounds.

The most desired outcome would be for sound urban planning to support a city’s economic and social development. This also determines the political role and status of Singapore’s future generation on the international stage. When young Singaporeans explore the world, they reminisce and feel proud of their country — which I guess, is the most significant impact that planning can have on the younger generations.