In highly dense and fast-growing metropolitan areas, such as Brisbane, Hong Kong, Melbourne, Singapore, and Tokyo —land is at a premium. Planning agencies and land owners and real estate developers must explore innovative strategies to optimise every square metre of space. In the education sector, high-rise schools have emerged as a compelling solution.

A Response to Urban Density and Land Economics

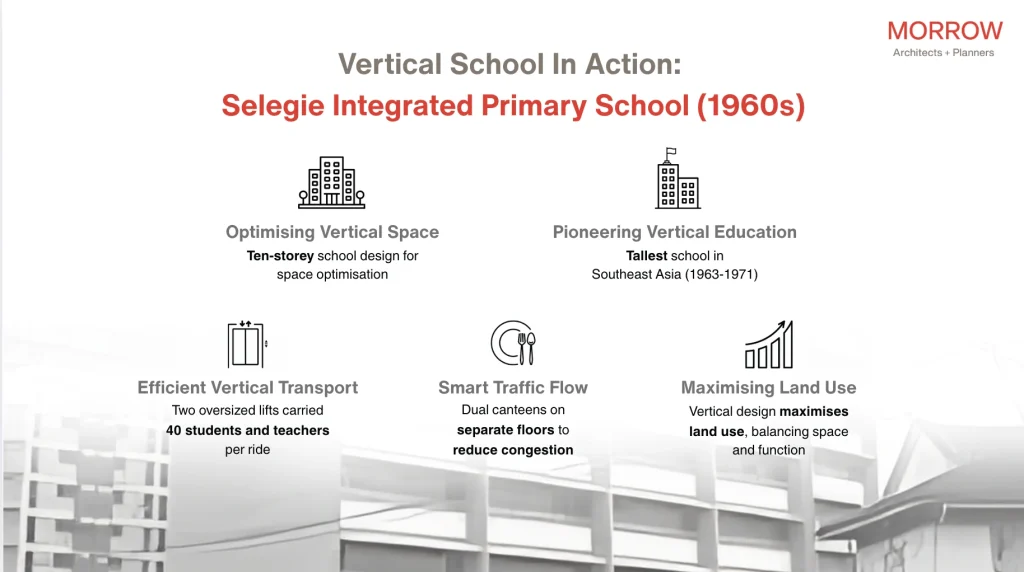

In Singapore, the idea of high-rise schools has been evolving for decades as a practical response to limited urban land. A notable early example is Selegie Integrated Primary School, constructed in the 1960s. At 10 storeys tall, it was the tallest school in Southeast Asia between 1963 and 1971, offering valuable design lessons that still inform today’s urban education planning. Selegie’s design and operations highlighted both the challenges and opportunities of vertical school models, many of which have shaped how high-rise schools are planned today.

Key design highlights of Selegie Integrated Primary School:

This and many newly-built and upcoming high-rise schools demonstrate that high-rise designs are no longer a rarity but rather a viable solution to modern urban challenges, where land parcels are limited, expensive, and highly contested. Unlike traditional campuses, vertical schools occupy compact footprints while delivering diverse programmatic functions. By planning classrooms, laboratories, collaborative learning zones, and recreational facilities across multiple floors, high-rise schools offer an alternative spatial paradigm – one that maximises educational yield per land unit without compromising functionality.

Image: Selegie Integrated Primary School, Singapore’s first high-rise school built in the 1960s by the Public Works Department (PWD)—pioneering vertical education infrastructure with ten stories. (Image source: selegieroadplan.wordpress.com)

Fast forward to 2018 in Singapore city centre, the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) expanded its presence with the development of a new 12-storey tower block. This high-rise building not only addresses the challenge of land scarcity by optimising vertical space usage, but also integrates with the city’s urban transport infrastructure.

Eight of the building’s 12 floors are dedicated to NAFA, providing the institution with approximately 7,700 square metres of space—an increase of 20 percent over its previous capacity. The remaining four floors are allocated for housing machinery and equipment and the Bencoolen MRT Station Entrance on the street level supporting the operation of the MRT station below, illustrating a co-development approach that benefits both educational and transport needs. The new tower is equipped with state-of-the-art studios and classrooms, significantly easing the school’s existing space constraints and enhancing its ability to deliver high-quality arts education.

Image: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts Tower Block, Singapore. (Project completed by RSP, Photo credit: MORROW)

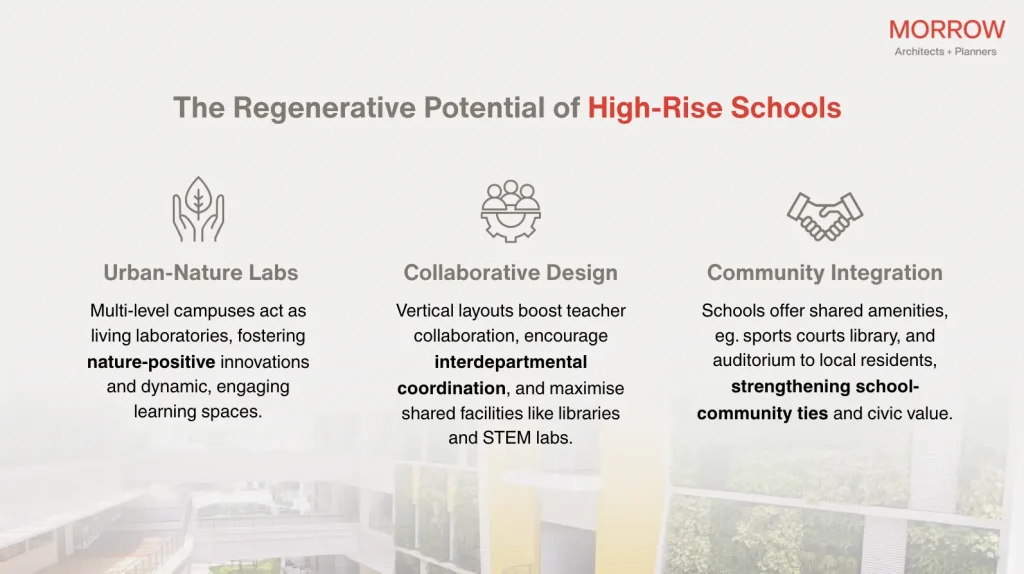

The Urban Regenerative Potential of High-Rise Schools

Beyond addressing land constraints, high-rise schools hold immense potential as catalysts for regenerative urbanism. While efficiency-driven design aims to reduce, optimise, and streamline, regenerative design seeks to create nature-positive outcomes and amplify environmental potential. As cities face increasing climate pressures and resource limitations, architects are integrating eco-friendly technologies, such as solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems, and skyrise greenery, not only to reduce the urban heat island effect but also to invite biodiversity back to the urban environment — into the design of high-rise schools.

This regenerative potential can be seen in three key areas:

Therefore, firstly, high-rise schools have the potential to become testbeds for how urban environments can coexist more harmoniously with nature, and living labs for students to test new nature-positive features alongside with environmental and digital technologies and initiatives to re-generate concrete-jungle urban environments. They can offer dynamic and stimulating learning environments for students. Multi-level structures can help create a sense of spatial awareness and curiosity for students. Vertical arrangements of various functions often prioritise light-filled, open spaces, collaborative and interactive spaces with further vista views on higher levels, while with more focus spaces such as laboratories on the lower levels.

Secondly, for teachers, high-rise designs often promote collaboration and resource-sharing. The vertical structure allows for close proximity between classrooms, which encourages spontaneous interactions among staff members, better coordination between subject departments, and a more efficient use of shared resources (such as libraries, STEM labs, and special education spaces).

Thirdly, high-rise school designs can provide environmental and social benefits for the surrounding community. Ideally, large areas on ground level and lower floors of vertical campuses can be used for community spaces, offering resources such as libraries, sports facilities, and open areas for the immediate surrounding community to have access to during non-school hours.

Together, these dimensions highlight how high-rise schools can move beyond mere land-saving solutions to become vibrant, multifunctional assets supporting environmental sustainability and social cohesion.

Biophilic Architecture as Educational Infrastructure

Biophilic design contributes to realising the regenerative capacity of high-rise schools. In compact city cores where access to greenery is limited, introducing natural elements into dense vertical structures enhances cognitive well-being, improves air quality, and stimulates a deeper connection between students and their broader urban environment. Incorporating green roofs, vertical gardens, and natural light is not just an aesthetic consideration, but also a psychological and pedagogical strategy. Studies have shown that access to nature and daylight positively impacts students’ mental well-being and academic performance. In cities where high-rise schools are becoming more common, we are already seeing progressive design solutions that emphasise biophilic principles—bringing nature into urban spaces through green facades, indoor plant walls, and courtyards. These elements create a more balanced environment and enable students to feel more connected to the outdoors, even in the heart of a dense urban landscape.

By building vertically, schools can reclaim space for greenery not only at ground level but also in the sky, redefining how urban districts experience nature. High-rise schools incorporate sky-rise greenery features, including rooftop gardens, vertical landscapes, and elevated recreational zones, which not only benefit students but also enhance the neighbourhood’s visual appeal, reduce the urban heat island effect, and improve air quality. Building upward helps reduce urban sprawl and positions these schools as beacons of vertical ecological design and sustainable urban growth.

Image: Biophilic Design blending educational spaces with natural elements at ESSEC Business School, One-North, Singapore. (Project completed at RSP, Image source: morrow.sg)

The design includes green façades, rooftop gardens, and layered terraces adorned with green trellis and raised planting areas, incorporating casual seating spaces adjacent to flowering plants. These green interventions do more than soften the building’s aesthetic; they regulate ambient temperatures, offer shaded learning zones, and encourage passive ventilation. Pockets of open-air breakout spaces and daylight-filled amphitheatres provide students and faculties with immersive, health-promoting learning environments that blur the boundary between built and natural elements.

This approach is emblematic of design principles, where passive strategies are combined with contextual sensitivity to optimise the advantages of natural elements for conducive learning, teaching, and interacting with each other and with the public at large.

While initial construction costs of high-rise schools can be higher, due to vertical circulation systems, safety requirements, and structural demands, these are offset by long-term efficiencies and ecological benefits. More importantly, such buildings present an opportunity to reimagine educational infrastructure as green vertical anchors—catalysts for regenerative urbanism and holistic student development.

Image: Green roofs at INSEAD campus, One-North, Singapore. (Project completed at RSP)

Challenges and Transformative Potential

High-rise schools do present certain challenges, both in terms of cost and functionality. Yes, the need for additional infrastructure, such as general-use lifts, specialised large-capacity elevators for multi-floor classroom transfers, and specialised safety features, can drive up initial construction costs and occupy floor area that could otherwise be used for classrooms, laboratories, offices, and other core functions. Moreover, design complexity increases as architects and engineers work to create safe, functional spaces within a vertical structure while ensuring that universal accessibility and circulation are optimised for large numbers of students. However, these costs are often offset by more savings in high land costs, potentially lower building envelope-to-floor area ratios, more efficient facility management, and the long-term value high-rise schools bring by maximising urban land use.

There is also a need to demystify the notion that high-rise schools only thrive in ultra-dense cities like Hong Kong, Singapore, or centralised first-tier cities in Australia. Increasingly, city governments in less densely populated and emerging Southeast Asian cities are showing foresight by exploring high-rise school development. This reflects growing confidence in the cost-effectiveness and strategic value of the high-rise school model.

Towards a Vertical Regenerative Pedagogy

High-rise schools offer far more than a spatial solution to land scarcity. When designing with regenerative and biophilic design principles, they become transformative models for the future of educational institutions in urban settings. They represent a shift in urban and architectural thinking—from efficiency to reconnection with nature, from enclosure to openness, and from building for use to building for experience and holistic positive impact.

As cities across the globe contend with the challenges of density, climate, and equity, high-rise schools can stand not only as efficient urban solutions but as beacons of a regenerative urban future, where learning, nature, and community are interwoven from the ground up.

Read the full article: Rise of Vertical Schools in Asia as Space Limits Spur Efficient Urban Solutions.

Explore more of MORROW in the media.

With nearly 20 years of practice in Sydney and Singapore, Dr Cam has established himself as a seasoned professional in the field of sustainable architecture and urban design. His expertise encompasses a diverse array of project types and scales – from city planning and township development to innovation districts, university campuses, mixed-use complexes, housing precincts, and individual buildings. This breadth of experience reflects his versatility and depth of knowledge.

Among his notable projects are ESSEC Business School, Jurong Innovation District Master Plan, Guangzhou Knowledge City, Saigon Sports City, High-rise Green Data Centre, and multi-storey Floating Data Centre in Singapore.